Images source:

1-Toronto Transportation Services – University avenue, Toronto

2-Toronto Transportation Services – York Street Green Gutter

Green Streets Program Goals

Toronto is increasing the city’s climate resilience with an equity-based Green Streets Program. Established in 2017, Toronto’s Green Streets Program integrates green infrastructure into the design of its streets, sidewalks, and boulevards to reduce air temperatures, enhance air quality, and manage stormwater in neighbourhoods across the city.

This green infrastructure is built into the City’s right-of-way which includes roads, curbs, and sidewalks; all of the publicly owned land that stretches from one property line to another. By reimagining how these spaces are designed and managed, Toronto is replacing traditional infrastructure with features that reduce urban heat islands (UHIs), manage stormwater, and improve water quality.

The City is giving priority to neighbourhoods that can benefit the most from green infrastructure in terms of stormwater management, air quality, social equity, tree canopy distribution, and climate resilience.

Building Climate Resilience

With human-induced global warming, air temperatures and the risk of flooding are increasing in many Canadian cities. Flooding is also becoming a greater concern in the city. In July 2024, for example, a flash flood led to power outages and almost $1 billion in insured damages.

Extreme heat events and flooding resulting from extreme weather and a dense urban environment motivated the City to plan how its rights-of-way could deliver environmental and social benefits. Green streets integrate features such as bioswales, permeable pavement, rain gardens, and bioretention assets, that can capture and filter stormwater while also cooling surrounding air through evapotranspiration.

Initiating a Green Streets Program

Toronto’s work on green streets began in 2013 after 60 mm of rain fell overnight and the Don River flooded some of the city’s major highways including the Don Valley Parkway.

“ This large storm gave rise to a City Council directive to develop green infrastructure standards to help manage the city’s stormwater in the right-of-way,” explained Kristina Hausmanis, Senior Project Manager, Green Streets Program, City of Toronto.

From 2013 to 2017, City Planning and Toronto Water collaborated to develop Green Streets Technical Guidelines while also piloting green infrastructure projects. Early work focused on large, underused right-of-way areas such as traffic islands. These were converted into bioretention sites by removing excess asphalt and adding curb cuts to direct runoff on to the greenery.

When a new General Manager, who had experience with Seattle’s Green Streets Program, joined Transportation Services, the Green Street vision was expanded.

“ With the new General Manager on board, it was decided that the Transportation Division, which has responsibility for the city’s right-of-way, should play a bigger role in the implementation of green streets infrastructure, ” explained Hausmanis. “ To scale up the program, it was recognized that we needed a clear governance model and defined asset ownership.”

Multi-Sectoral Collaboration

The installation and maintenance of green streets infrastructure involves several divisions within the City so there is a need to work collaboratively across all divisions. A governance model was established in 2017 that brought several divisions together including Transportation Services, Engineering and Construction Services, City Planning, Parks, Forestry, and Recreation, (now Environment, Climate and Forestry), and Toronto Water.

A Steering Committee was created, supported by a staff-level working group, to coordinate the development and implementation of green streets infrastructure across the city. As the primary owner of the right-of-way assets, Transportation Services assumed leadership for the Green Streets Program.

“ We, in Transportation Services, own and are responsible for the green infrastructure assets in the right-of-way, but other divisions are essential to the project’s success,” offered Hausmanis. “ For example, Toronto Water is responsible for flushing out catch basins going into green infrastructure and Urban Forestry takes care of street trees.”

“ The City has also partnered with non-profit organizations. For example, the City is collaborating with the Toronto Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) via their Sustainable Technology Evaluation Program (STEP) on the evaluation and monitoring of green infrastructure sites in the city,” explained Hausmanis.

The City has also collaborated with non-profit organizations on its workforce development program, GreenForceTO, that was initiated in 2021. Transportation Services partnered with two local Employment Social Enterprises, RAINscapeTO and Building Up, to hire and train individuals from Neighbourhood Improvement Areas in the city and people experiencing barriers to employment, for the maintenance of green streets infrastructure. Neighbourhood Improvement Areas are neighbourhoods that need support to improve the wellness of their residents based on economic opportunities, social development, health, community engagement, and physical characteristics of their communities.

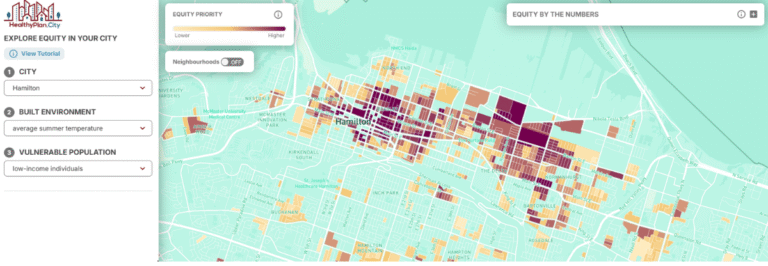

Prioritizing Neighbourhoods for Green Infrastructure

With over 5400 km of roadways, Toronto required a systematic approach to prioritize locations for green infrastructure.

“ We are moving from a model that was based solely on opportunities to pilot green infrastructure to one that considers program benefits,” explained Anisha Patel, Project Manager, Green Streets Program, City of Toronto. “ We are looking for neighbourhoods that would benefit most from green infrastructure interventions by assessing both vulnerabilities and opportunities in neighbourhoods across the city.”

This approach evaluates where green infrastructure can be most beneficial at reducing climate vulnerabilities, improving the quality of life for residents, and decreasing social inequities, while also considering the physical opportunities for installation.

This selection process involves three stages:

- Geospatial Analysis: With the first stage, a model is used to prioritize projects based on the co-benefits that can be gained with green infrastructure. This model allocates a score for five green infrastructure co-benefits:

- Stormwater Management which is based on data related to combined sewer overflow areas, storm sewers that flow into environmentally sensitive areas, impervious surfaces, and rainfall distribution;

- Air Quality which is based on data related to the density of senior or childcare facilities within areas with high levels of traffic-related air pollution;

- Tree Canopy Cover based on tree canopy distribution;

- Social Wellness which is based on “Neighbourhood Improvement Areas” identified by the City; and

- Climate Resilience which is based on extreme heat vulnerability maps and areas identified as vulnerable to storm-related floods.

- Geospatial Analysis: With the first stage, a model is used to prioritize projects based on the co-benefits that can be gained with green infrastructure. This model allocates a score for five green infrastructure co-benefits:

Projects in the top percentile are then selected for the second stage.

- Desktop Analysis: In the second stage, the suitability of the site for green infrastructure implementation is evaluated using factors such as space available, soil conditions, site coordination conflicts, and public visibility.

- Stakeholder Coordination: The third stage draws upon the expertise of the Green Streets Working Group and others to identify the scope and budget needed for the project and to coordinate implementation.

The City is in the process of developing key performance indicators and implementation processes to guide how green infrastructure will be installed and evaluated in these targeted neighbourhoods.

Community Engagement

Community engagement plays an important role in Toronto’s Green Streets Program. The City works directly with communities. It offers choices to impacted residents to select the green infrastructure options that work best for them.

“ Some neighbourhoods have open ditches that can be transformed into bioswales,” said Hausmanis. “ When the City installs these bioswales, residents are provided with native and suitable plant options, which they are expected to maintain after installation. However, if residents prefer not to have a garden, they can opt for sod, which still provides the water quality benefits of green infrastructure.”

Challenges and Lessons Learned

The Green Streets team has learned that project feasibility varies by location.

“ Suburban areas such as Etobicoke and Scarborough provide more space for green infrastructure than Toronto’s urban core,” stated Hausmanis.

City staff have learned that education and outreach are important for public acceptance of green infrastructure.

“ While attitudes are shifting towards natural gardens, many residents still prefer the look of manicured sod,” said Hausmanis. “ It is important that we educate residents about the benefits of green infrastructure. We plan to develop educational materials such as infographics to help them understand the value of these features.”

There have also been challenges with utility contractors and construction activity damaging green infrastructure assets.

“ The City has the Municipal Consent Requirements that outline requirements for working within the city right-of-way. However, these requirements do not reference how developers or utility contractors are to work within or around green infrastructure assets,” explained Patel. “ We need to update these requirements to ensure that green infrastructure is protected when it is worked around”

Funding

The cost of green infrastructure is project dependent. The standard cost of reconstruction in the right-of-way is calculated and the Green Streets Program covers the additional cost of incorporating green infrastructure, which is typically about 30-40% more for linear green infrastructure.

“ We have not been able to estimate the cost savings created with green infrastructure yet,” noted Patel. “ The reduction in air temperature and stormwater management are incremental with each project, so it is hard to say how much harm and damage is being prevented with each project. Over time and cumulatively, we expect that there will be considerable financial and health savings, but we don’t have the data to demonstrate that yet.”

Green Streets Features

Toronto’s green infrastructure features include the following:

- Continuous Soil Trenches and Stormwater Tree Trenches: Trenches placed beside walkways that collect stormwater into planters and direct it to trees.

- Bioretention Assets: Garden-like structures including cells, planters, and curb extensions that collect and filter stormwater, allowing some of the water to support native plants.

- Bioswales: Linear, vegetated channels that slow down, treat, and store stormwater temporarily.

- Enhanced Grass Swales: A gently-sloped channel that reduces stormwater runoff and cleans stormwater as it flows.

- Green Gutters: Shallow, vegetated planters installed along a street’s length to capture and filter runoff while separating transportation corridors (e.g., vehicle traffic, bikes, transit lanes).

- Vegetated Filter Strips: Gently-sloped, vegetated areas that are installed adjacent to impervious surfaces to treat and reduce stormwater runoff.

- Permeable Pavement: Paving materials that consist of small pores and allow rainwater to drain into an aggregate storage layer temporarily before being conveyed into native soil or other drainage systems. These materials include permeable interlocking concrete pavers, porous asphalt, and pervious concrete.

- Infiltration Trenches: An underground trench made up of geotextile-lined excavations that temporarily holds and treats stormwater.

- Rain Gardens: A shallow, sunken planting bed composed of highly permeable soil that collects rainwater, filters it through the soil and plants, and prevents standing water.